(Click here to read Part 1: Growing Out of the Orphanage)

It was the turn of the century and Samuel Levy, President of the Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society, knew that “the glorious work of individualizing children” was due for a modernizing leap forward. A lawyer who worked largely pro-bono with poor families, Levy had accepted his position on the condition that he be free to pursue whatever reforms he saw fit. “We have arrived at the stage of our existence when something more should be done than merely clothe, feed, and plainly educate,” he remarked in 1903. This aim required more than just internal adjustments at existing institutions; it necessitated a new paradigm––and a new environment.

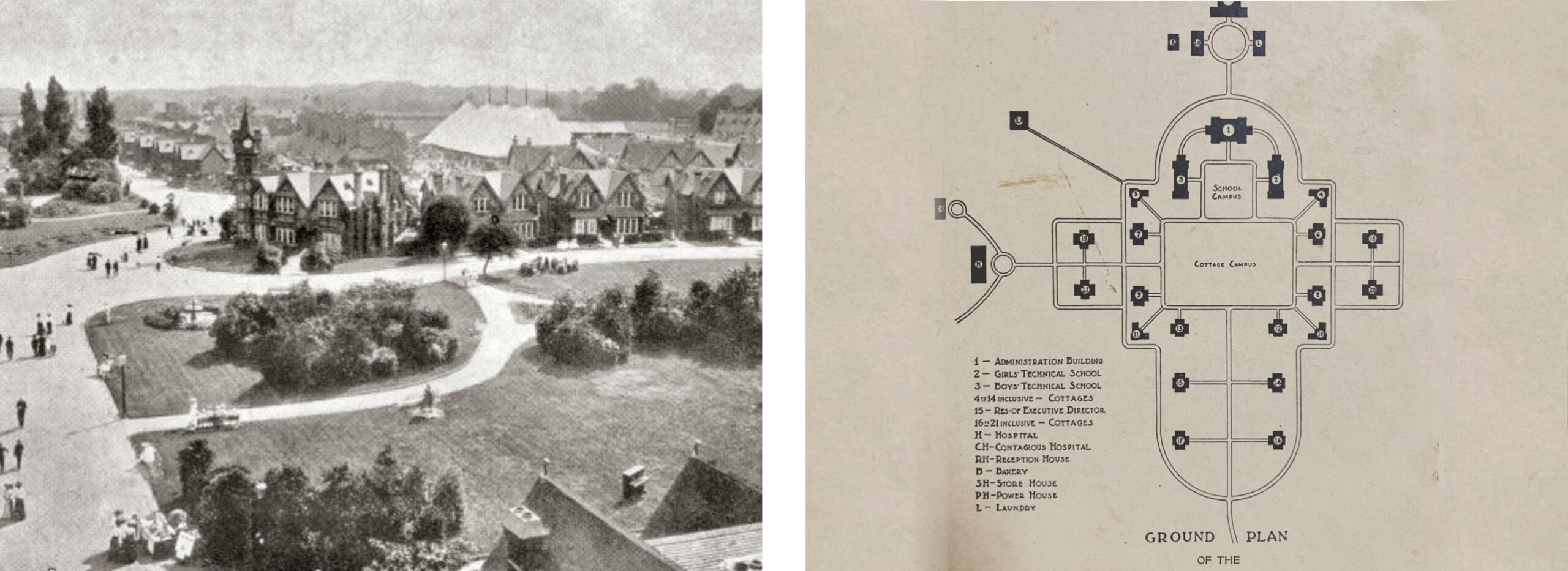

Left: Cottages at the Barkingside School in East London, an inspiration for the Pleasantville Cottage School. Right: Early diagram of the Pleasantville campus from the 1932 annual report of the Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society.

While visiting England, Levy toured the Barkingside School. Set in a Jewish enclave in East London, Barkingside was the first children’s institution to use the cottage-plan. “It seemed that no child was lost in the mass,” Levy noted. The cottage system allowed for close-knit, family-like living despite the facility’s significant number of children. Residents benefitted from the personal attention and belonging that came from cottage life––and also from resources only possible in a large institution, such as an on-site school, medical facilities, and recreation offerings.

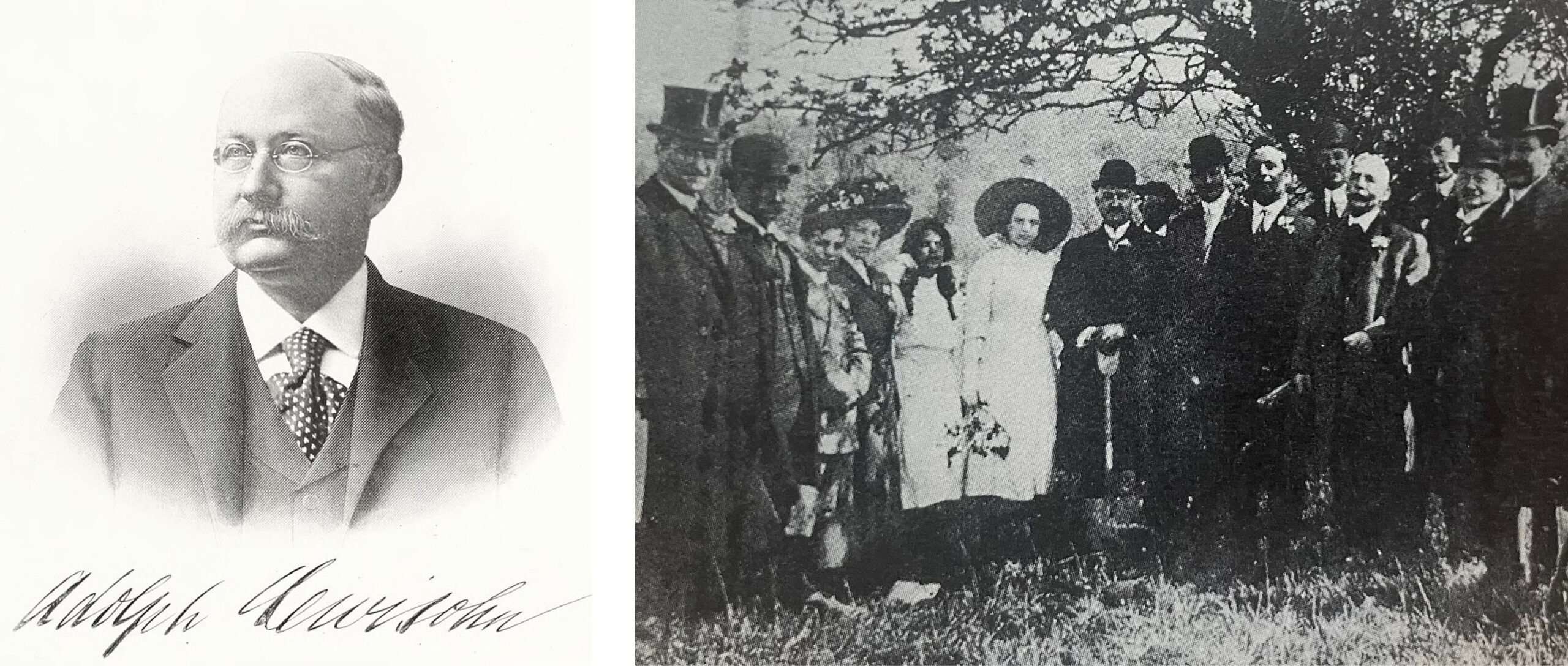

Levy believed he’d seen the way forward for the youth in his care, and sold his vision to copper magnates and HSGS Trustees Leonard and Adolph Lewisohn. The ambitious vision required not just money or buildings but––crucially––space. 150 sites were reviewed before settling on a 160-acre tract in Pleasantville, which was then largely rural. Levy also sought to refine the philosophical and pedagogical principles of what would become the Pleasantville Cottage School, organizing a conference of experts and sending a staffer abroad to study the latest teaching methods from Europe.

Left: German Jewish immigrant, banker and philanthropist, Adolph Lewisohn. Right: Groundbreaking ceremony at Pleasantville Cottage School c. 1910.

Revised many times before satisfying all involved, the educational plan was nothing short of pioneering––“a radical advance in progressive education,” as one visiting expert put it. Every Pleasantville resident would be expected to graduate, following a curriculum that combined traditional academic subjects, foreign languages (including Hebrew), and Jewish history. Most notable at the time was the program’s robust vocational component, offering woodworking, machine shop, electric shop, and mechanical drawing. Girls could take sewing, costume design, millinery, and embroidering, in addition to office skills like stenography and typewriting. While these gendered divisions are now outdated, such training provided skills immediately useful on the job market.

Campus residents learned valuable skills like woodworking and sewing.

In the meantime, noted architect Harry Allan Jacobs was employed to draft plans, which featured a tree-lined entry road, stately cottages with a column-supported front porches, and an elegant, semi-circular administration building in the Italian Renaissance style. In preparation for life in the cottages, boys and girls were taught how to cook and began practicing domestic routines. The architectural plan responded directly to the input of house mothers, who rehearsed and experimented with cottage routines endlessly.

Early renderings of the Pleasantville cottages featured on postcards.

Then came the big day: July 1, 1912. Nearly 500 youth made a parade down Broadway waving American flags as a marching band played. They walked in cottage formation to the railroad station on 125th street for the ride north into the country, a setting most of the youth had never seen before. The first impressions one of resident were captured in The Children They Gave Us, a 1972 history of JCCA: “We were like bugs flying all over. We ran in and out of all the cottages. We chased each other across the square. We climbed inside huge ice boxes which looked bigger than a whole East Side apartment. We got inside the furnaces. We jumped on the beds and flushed the toilets. We were explorers in a new world.”

Professionals in the field were no less impressed, coming from across Europe and North America to study it. One executive called it “undoubtedly the best equipped institution for children in the world.” Within five years, three new institutions were constructed on its precise pattern. President Taft visited. Harvard University requested copies of Pleasantville’s plans and practices for inclusion in its Social Ethics Museum. A dozen years after its founding, PCS innovated again by establishing the nation’s first psychiatric clinic in a child care setting.

More than a century later, the Pleasantville Cottage Campus remains vital and thriving, having added programs for youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities, autism, complex trauma, and histories of commercial sexual exploitation and sexual abuse. To get involved in JCCA’s next century of pioneering care, click here.